Use of behaviour change theory or constructs in basing intervention strategies to encourage older adults in physical activity (PA) has often resulted in greater effectiveness (Antikainen, 2011; Carlson et al., 2012; Chase, 2013; Müller & Khoo, 2014; Stewart et al., 2007; Yeom & Fleury, 2014). The belief in one’s ability to perform a physical activity also known as perceived behaviour change (PBC), a behavioural psychological mediator, resulted in increased physical activity participation (Antikainen, 2011) supporting the efficacy of theory-based motivational PA interventions (Weber & Sharma, 2011). To examine the appropriateness of a particular theory the following represents a summary of relevant theories which facilitates behaviour change.

Behaviour Change Theories

Key theories used for PA interventions are discussed in this section.

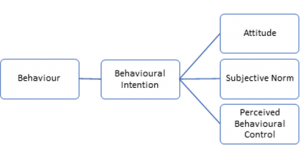

Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

This theory (Figure 1) establishes that participants intentions (motivation) to engage in PA is greatly influenced by their attitude towards outcomes of a behaviour, subjective norm and their perceived behavioural control of the activity (Ajzen, 2015). The subjective norm represents the perceived social pressure to participate in an activity. Perceived behavioural control (PBC) represents the extent of a participant’s belief in their ability to perform an activity (Ajzen, 2015; Motalebi, Iranagh, Abdollahi, & Lim, 2014).

Figure 1: Theory of Planned Behaviour ((Ajzen, 2015))

This theory was used in a non-gamified web intervention for sedentary individuals to enable behavioural control facilitating a feeling of ownership thereby improving program engagement (Irvine, Gelatt, Seeley, Macfarlane, & Gau, 2013). Priming of users intentions assisted with improving an individual’s intention to participate in physical activity and increased the duration of use of an exergame (Chen, King, & Hekler, 2014).

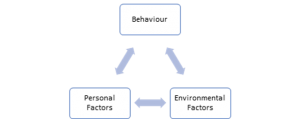

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)

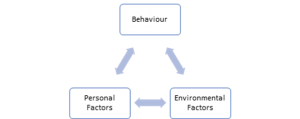

This learning theory (Figure 2) is based on the premise that people learn by observing others. Observed human behaviour is influenced by the dynamic interplay between personal factors (self-efficacy), behavioural factors, and environmental factors (Bandura, 2002). From the health behaviour domain, the SCT theory posits that human motivation, behaviour and well-being is influenced by one’s self-efficacy beliefs (ability to complete a task, experience of mastery or being in control and verbal persuasion or feedback) which operate in conjunction with goals, outcome expectations, and environmental barriers and facilitators (Bandura, 2004).

Figure 2: Social Cognitive Theory

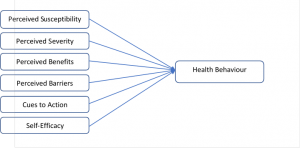

Health – Belief Model (HBM)

This theory is a psychological behaviour change model (Figure 3) which posits that an individual’s beliefs with regard to their health (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers and self-efficacy about their health problems) influence their readiness to take action (Glanz, 2015; Janz & Becker, 1984) to overcome their health challenges or illness.

Figure 3: Health – Belief Model (Glanz, 2015; Janz & Becker, 1984)

Transtheoretical Model (TTM)

This theory is a psychological behaviour change model (Figure 4), which posits that an individual’s beliefs with regard to their health (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers and self-efficacy about their health problems) influence their readiness to take action (Glanz, 2015; Janz & Becker, 1984) to overcome their health challenges or illness.

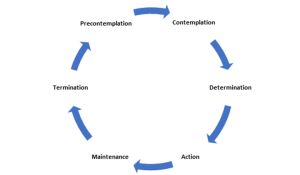

This theory (Figure 5), also known by the term “stages of change” (SOC) argues that an individual’s readiness to change their health behaviour occurs gradually through the progressive steps of pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, and termination (Motl, 2014). The SOC essentially defines one’s readiness for behaviour change beginning with pre-contemplation (when the individual has not considered any behaviour change), to considering a behaviour change (contemplation), preparing to commit oneself to the behaviour change, actionable activity initiating the behaviour change, maintaining the behaviour change and ending with termination wherein the new behaviour has become the norm. Fish’ n’ Steps (Lin, Mamykina, Lindtner, Delajoux, & Strub, 2006), an interactive computer game investigated the TTM model in overcoming a sedentary lifestyle by encouraging participants to initiate PA where their daily step count led to the growth and activity of an animated character of a fish in a fish tank.

Figure 4: Transtheoretical Model (Stages of Change)

In this study, participants in the pre-contemplation stage indicated less number of steps compared to those in the termination stage, where the indicators of progression in the animated character of the fish contributed to maintaining their attitude towards increased step count (Lin et al., 2006).

Fogg Behaviour Model (FBM)

In the design of persuasive technologies, the combination of motivation, ability and trigger (Fogg, 2009) (Figure 5) needs to be present for a behaviour change to occur. This implies that an absence of any one of these will prevent the occurrence of an actionable behaviour. While this model has been studied in the design of persuasive technologies and referenced this model in this section from the perspective of the design of gamification applications. The aim of gamification strategies is to persuade and encourage users to initiate and maintain PA, thereby serving as a trigger and fostering the motivation to be able to do the activity (Hamari & Koivisto, 2013; Schoeppe et al., 2016).

Figure 5: Fogg Behaviour Model (B = M+A+T)

Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

SDT, an evolving theory of human motivation (Table 1), posits that for growth and personality integration, the three basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness must be satisfied (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Autonomy represents a sense of freedom or being in control, competence establishes a sense of ability to do things competently and, relatedness establishes a sense of association with others (Ryan & Deci, 2000). SDT has been applied to video games (Ryan, Rigby, & Przybylski, 2006), which has shown that the perceived attractiveness of games is influenced by a player’s need satisfaction related to fulfilment of the psychological needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness. Within video games and gamification, perceptions of competence and autonomy are also related to the intuitive nature of game controls and the sense of presence or immersion in the participants’ experiences (Kappen, Johannsmeier, & Nacke, 2013; Ryan et al., 2006).Table 1: Self-Determination Theory (Deci, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000).

|

Basic Psychological |

|||||

|

Autonomy |

Competence |

Relatedness |

|||

|

Cognitive Evaluation |

|||||

|

Intrinsic |

Need |

||||

|

Organismic Integration |

|||||

|

Amotivation |

Extrinsic |

Intrinsic Motivation |

|||

|

Non-regulation |

External Regulation (compliance, external rewards and |

Introjected Regulation (self-control, ego-involvement, approval |

Identified Regulation (value of an activity, endorsement of |

Integrated Regulation (accepting of awareness, synthesis with the |

Intrinsic Regulation |

Table 1: Self-Determination Theory (Deci, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000)

In the context of SDT, intrinsic motivation refers to engaging in an activity because it is inherently interesting or enjoyable, and extrinsic motivation refers to doing something because it leads to a separable outcome (Deci, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET) posits that the need for competence and autonomy is rooted in intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation could be influenced by social contextual and extrinsic factors such as rewards, praise, encouragement and feedback thereby fostering competence (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Ryan, Frederick, Lepes, Rubio, & Sheldon, 1997). Additionally, these feelings of competence would not foster intrinsic motivation unless accompanied by a sense of autonomy (Ryan & Deci, 2000). From an exercise motivation perspective, increased enjoyment and adherence in PA were associated with activities fostering intrinsic motivation elements of competence, challenges and social interaction (Edmunds, Ntoumanis, & Duda, 2006; Ryan et al., 1997).

The Organismic Integration Theory (OIT) (Table 1) illustrates the taxonomy of extrinsic motivation and posits that people tend to internalise their experiences when being rewarded or externally motivated for participating in mundane or uninteresting activities (Deci, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Within the context of gamification technologies for PA, I decided to focus on SDT because the primary research question aimed to identify whether gamification technology would foster intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in older adults?

The following post gives an overview of persuasive technologies for PA motivation and gamification directed towards building the theory of effective gamification. SDT (Deci, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000) was used as the foundational theory to develop the KEG (Kappen & Nacke, 2013), which was eventually used to design a gamified PA technology tailored for the older adult demographic.

References

Ajzen, I. (2015). The Theory of Planned Behavior. In P. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology : Volume 1 (Vol. 1, pp. 438–460). London: SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446249215.n22

Antikainen, I. E. (2011). Investigating the Effectiveness of Physical Activity Interventions for Older Adults. Georgia State University.

Bandura, A. (2002). Social Cognitive Theory of Mass Communication. In J. Bryant & D. Zillman (Eds.), Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research (2nd ed., pp. 121–153). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bandura, A. (2004). Health Promotion by Social Cognitive Means. Health Education & Behavior : The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 31(2), 143–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660

Carlson, J. a, Sallis, J. F., Conway, T. L., Saelens, B. E., Frank, L. D., Kerr, J., … King, A. C. (2012). Interactions between psychosocial and built environment factors in explaining older adults’ physical activity. Preventive Medicine, 54(1), 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.10.004

Chase, J. D. (2013). Physical Activity Interventions Among Older Adults: A Literature Review. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice: An International Journal, 27(1), 53–80.

Chen, F. X., King, A. C., & Hekler, E. B. (2014). “ Healthifying ” Exergames : Improving Health Outcomes through Intentional Priming. In Proc. of CHI 2014 (pp. 1855–1864).

Deci, E. L. (2008). Self-determination theory: A Macro-theory of Human Motivation, Development and Health. Canadian Psychology, (49), 182–185.

Edmunds, J., Ntoumanis, N., & Duda, J. L. (2006). A Test of Self-Determination Theory in the Exercise Domain. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36(9), 2240–2265.

Fogg, B. J. (2009). A Behavior Model for Persuasive Design. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology – Persuasive ’09 (p. 1). New York, New York, USA: ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/1541948.1541999

Glanz, K. (2015). Important Theories and Their Key Constructs: Health Belief Model. Retrieved from http://www.esourceresearch.org/Default.aspx?TabId=731

Hamari, J., & Koivisto, J. (2013). Social motivations to use gamification: An empirical study of gamifying exercise. In 21st European Conference on Information Systems, ECIS 2013. Association for Information Systems. Retrieved from http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84926428512&partnerID=40&md5=9acc2c3e0955c162e001bc18a556444a

Irvine, A. B., Gelatt, V. A., Seeley, J. R., Macfarlane, P., & Gau, J. M. (2013). Web-based intervention to promote physical activity by sedentary older adults: randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(2), e19. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2158

Janz, N. K., & Becker, M. H. (1984). The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Health Education & Behavior, 11(1), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019818401100101

Kappen, D. L., Johannsmeier, J., & Nacke, L. E. (2013). Deconstructing “ Gamified ” Task-Management Applications. In Gamification 2013 (pp. 1–4).

Kappen, D. L., & Nacke, L. E. (2013). The Kaleidoscope of Effective Gamification: Deconstructing Gamification in Business Applications. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Gameful Design, Research, and Applications – Gamification ’13 (pp. 119–122). https://doi.org/10.1145/2583008.2583029

Lin, J. J., Mamykina, L., Lindtner, S., Delajoux, G., & Strub, H. B. (2006). Fish ’ n ’ Steps : Encouraging Physical Activity with an Interactive Computer Game. In In Proceedings of the 8th international conference on Ubiquitous Computing (Ubi- Comp’06) (pp. 261–278).

Motalebi, S. A., Iranagh, J. A., Abdollahi, A., & Lim, K. (2014). Applying the theory of planned behavior to promote physical activity and exercise behavior among older adults. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 14(4), 562–568.

Motl, R. (2014). Transtheoretical Model. In R. C. Eklund & Gershon Tenenbaum (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Sport and Exercise Psychology (pp. 768–770).

Müller, A., & Khoo, S. (2014). Non-face-to-face physical activity interventions in older adults: a systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 11(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-11-35

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Ryan, R. M., Frederick, C. M., Lepes, D., Rubio, N., & Sheldon, K. M. (1997). Intrinsic Motivation and Exercise Adherence. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 28(4), 335–354.

Ryan, R. M., Rigby, C. S., & Przybylski, A. (2006). The Motivational Pull of Video Games: A Self-Determination Theory Approach. Motivation and Emotion, 30(4), 344–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-006-9051-8

Schoeppe, S., Alley, S., Van Lippevelde, W., Bray, N. A., Williams, S. L., Duncan, M. J., & Vandelanotte, C. (2016). Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: a systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 13(1), 127. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0454-y

Stewart, A. L., Verboncoeur, C. J., Mclellan, B. Y., Gillis, D. E., Mills, K. M., King, A. C., … Bortz, W. M. (2007). Physical Activity Outcomes of CHAMPS II: A Physical Activity Promotion Program for Older Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 56(8), 465–470.

Weber, A. S., & Sharma, M. (2011). Enhancing Effectiveness of Physical Activity Interventions Among Older Adults. American Journal of Health Studies, 26(1), 25–36.

Yeom, H.-A., & Fleury, J. (2014). A Motivational Physical Activity Intervention for Improving Mobility in Older Korean Americans. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 36(6), 713–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945913511546